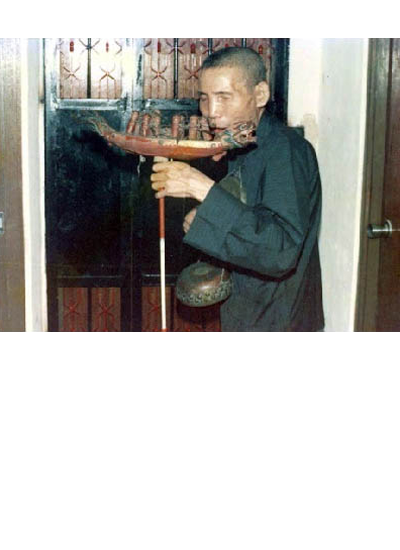

Yuen Siu-fai is a renowned Cantonese opera star. He was born in Foshan, Guangdong, and came to Hong Kong with his father at a young age. Yuen made his debut as a child prodigy at the age of seven in film before taking up Cantonese opera, with a career spanning over sixty years. He had received numerous awards for his achievements. He devotes much effort in the transmission of Cantonese opera and education of young singers. He also works with scholars to foster research of Cantonese opera and song art. Yuen is highly proficient in Naamyam singing, and has acknowledged the inspiration from Douwun. In the 1970s, he frequently went to the streets of Mongkok to listen to Douwun. He began learning from his singing style, and was extremely impressed by him. Yuen has recorded many Naamyam songs.

-

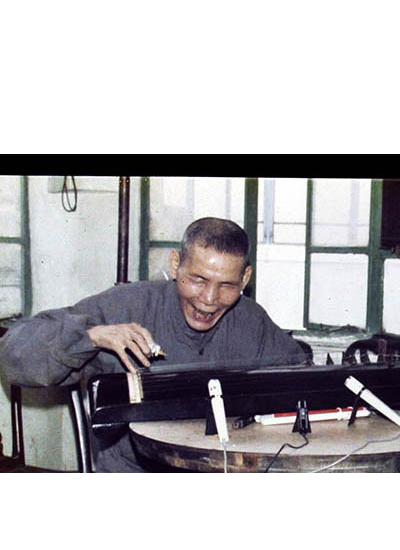

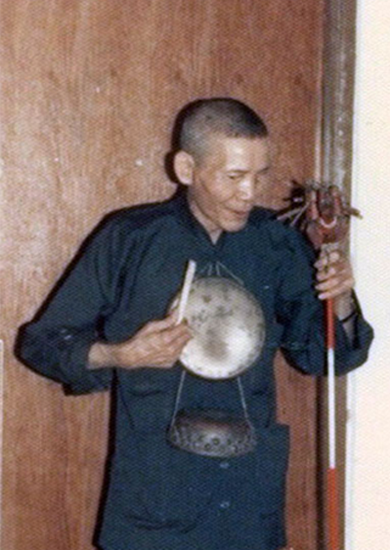

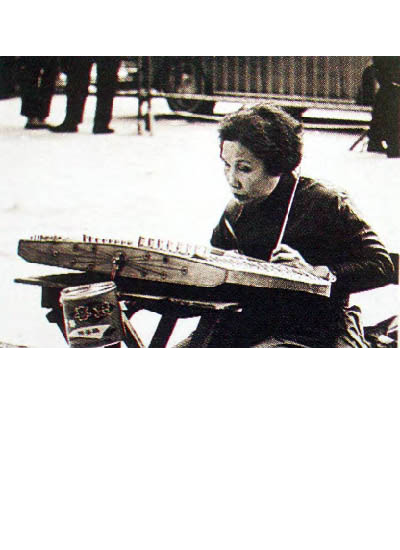

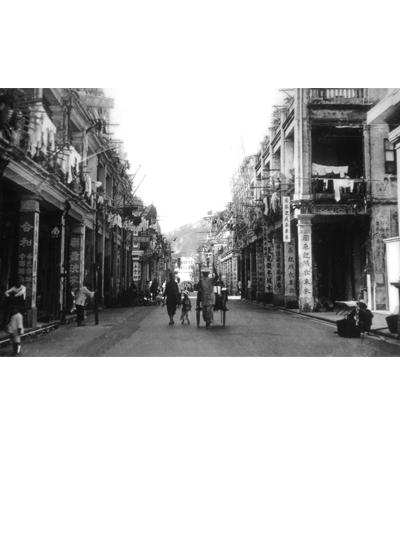

Since the 1970s, Nanyin began to be re-discovered by scholars in Hong Kong and overseas. Douwun’s artistic achievement has become recognized. From singing on the streets, he went on to more formal performance venues, such as the City Hall, Goethe Institute, St John’s Cathedral, and the Chinese University of Hong Kong. In the Hong Kong Art Festival of 1973-1974, Nanyin was part of a programme that presented traditional culture.